Omicron

An overwrought contact tracing form and medical journal of my first five months with Long Covid in 2022

Dear all of you1:

June 13

You’re sitting across from us at the charging station while waiting for our boarding announcement. I am talking to work husband about how best to turn sinigang bloody red. The Muslim woman wearing a batik shawl beside you strikes up a conversation. I notice this happening and laugh and point it out to work husband who also laughs with me. You seem to be doing fine so we don’t come to your rescue. You are nodding your head and your eyes suddenly widen. You excuse yourself and come to us when our boarding station is announced over the PA system. You tell us about the conversation you just had: The woman said she had gotten covid twice, most recently last October. You told her you had come down with it last January. Hearing this, she said, matter-of-factly, that covid will find you again in October, too. You ask me whether this is true. I raise an eyebrow at you and assure you that it isn’t true, or at least, I wouldn’t be able to know. I joke that maybe you had just met the personification of Ms. Rona herself, and, like an oracle casually portending doom, she’d come to warn you of a fate preordained and, therefore, impossible to escape.

June 14

My throat is hoarse from talking at the podium for three hours straight, my mask slipping down the bridge of my nose every six or so words. Back in our hotel room, I ask you if it’s possible for lunch to be served here instead of at the function hall. You reply that we needed to check out before noon. I pause at the threshold of the function hall with a plate full of food, hesitating at the sight of so many people eating lunch, exhaling an invisible aerosol cloud of microscopic, unalive, potentially infectious things. I glance towards a couch at the end of the long anteroom to my right and contemplate dining there alone. In the end, I acquiesce to social etiquette and eat mechado beside you, lowering and raising my mask up after every bite, knowing it accomplishes nothing. When I look back at it now, this is probably where it all started.

June 15

I ask you over pork nilaga for dinner whether it’s Mandarin or Cantonese I’m hearing from across the pool in this technicolor apartelle, not really expecting you to know, saying something just to keep the saliva from spoiling in my mouth. All the doors on this floor have Chinese characters on red construction paper hanging from them, and in front of one are two bald and topless Chinese men talking to each other loudly. They seem to be old friends on vacation or maybe they’re here for work. After dipping their toes in the cold water, their wrinkly bodies shuffle into their room. I congratulate myself for not thinking then of wet markets and pangolin meat and zoonotic diseases, but instead of Tony Leung and Leslie Cheung adrift in their little apartment in Argentina. I wouldn’t know, you say. I feel like a balloon about to burst and groan at you to finish the rest of my nilaga. You tell me to rest a while and try again. You grin at me, and your eyes shrink. Your hair is a mess. I pull my bowl back and smile at you, too.

June 16

We take a day trip to go island-hopping in Moalboal, the name rolling off my tongue too smoothly which meant I was pronouncing it wrong. I’d forgotten how much you had to simulate hiccupping to speak Bisaya correctly. You laugh at this, but I don’t tell you how I find it funny that someone who grew up in Binmaley needs a life jacket to keep afloat because I can’t swim myself. In the open water, we huddle close, clinging onto a lifesaver tugged by the boatman, egging us on in a language we don’t understand. We plunge our faces below the surface and marvel at the shimmering wall of sardines. I spot an underwater cliff to our left and the black unknown sprawling beneath and pull my head out of the sea. You float out into the blue where all the tourists are gathering until you are only an orange life jacket bobbing in the distance and I am alone, aimlessly adrift.

June 17

Our last stop before our flight back to Manila is Fort San Pedro. The air is thick and sweat sticks to my skin with salt. On top of the battlements, I marvel at how I’ve never hugged air so corporeal. I sit on a bench under a grilled roof that isn’t much of a roof. I feel the beginnings of an afternoon rain shower graze my cheek and fill my mouth with hair. Taking in the storm clouds rolling in and the largeness of this stone fort, I try mustering sympathy for the poor souls that must have drowned in the prison cells here but come up empty. Our coworker is taking photos of you straddling a brass cannon. I turn to face the wind and sense her snapping photos of me brooding. You walk up to me and I am smiling at you. You call me miss and laugh.

June 18

Back in Manila, I make breakfast for everyone because I know I won’t be back until early tomorrow morning. I caramelize cabbages and post them on my Instagram stories. I loiter around the house, bracing myself mentally for the onslaught of people later that evening, get bathed and dressed, and head out the door.

*

You’re the first performer to arrive at the venue. Your hair is glossy from perspiration and an Argentina football jersey hangs lousily from your shoulders. You have an adjective for a name. We are sitting beside each other at the bar counter. You tell me it’s your first time reading your poetry to an audience. I tell you I used to write. You do tarot card readings as a hobby and as a source of secondary income and fan a deck on the counter. You offer a free reading and I ask about my writing. You draw three cards, and their meaning together escapes me. You tell me all these worries I have about myself, about writing, I should just drop them and write. You’re feeling empty and disconnected from yourself because you’re not writing. Just write. I thank you for the reading and sip from my bottle of beer.

So why have you stopped writing?

I think about why for a moment. You know Elaine Castillo?

Not really.

America Is Not The Heart?

Ah, yes. I know her.

She said she stopped writing for four years after her dad died, refused to create art to process her grief, and only slowly got back into it by writing fan fiction, which explains why America Is Not The Heart’s prosody sounded so Wattpad-y to me.

So, you begin again tentatively. Who died?

Oh no, no one died, I explain in the jittery, apologetic way I talk, abundant with hand gestures. I pause before saying anything else, not for dramatic effect, but because I cringe at what I’m about to say.

More like, I was mourning a relationship that ended three years ago, and for once I decided I didn’t want to make art about my feelings. I just wanted to ride it out, to feel. But that’s alright now, I say defensively before you can respond. It’s been three years, I moved on completely after one.

We both take a swig of our beers before the stage calls for you.

*

Everyone is smoking at the front garden when it’s over. Hugs are exchanged, cheeks kissed. I begin to wonder how everyone knows each other. I think about how I don’t know anyone. I wonder whether there was a bootcamp all the gays attended that explains how they all know each other. I wonder whether it was a bathhouse, and it was my irrational fear of getting stealthed mid-doggy that kept me from this inner sanctum. I feel suddenly alone, a familiar feeling, almost but unlike a friend. I still don’t know why I keep inviting myself to places where I am unknown. Like now, in a van en route to Katipunan.

*

You bump into me as soon as I get here. You’re dressed in a garish orange, a baudy choice of apparel. You are hanging onto a friend’s shoulder as a crutch, mildly uncoordinated. You are inching claustrophobically close to my face, an average Filipino’s dick size away. I straighten my arm out in front of me to stop you. You ask me if I want to make out with you. I haven’t seen you in years.

No. Not here. Maybe another time.

Your friend thumbs through my hair and in my dissociated and overstimulated state, I ignore this breach of personal space.

I am nice, you say. You say this over and over again, like you’re trying to convince yourself, like you’ve only just discovered words. It’s like I’m talking to a toddler.

Your other friend lights a cigarette. I’m sorry, he says. We’re giving you lung cancer.

No, it’s fine, I say. I might be giving you covid.

Your friends produce a bottle of gin from seemingly nowhere and rinse your mouth with it. You take me for a walk through a thicket of bodies and smoke and noise so suffocating. I get my chance and escape to the restroom. I ensconce myself inside a concrete cubicle. I stare blankly at an empty bottle discarded on the floor. I need to go home.

At the Angkas pickup point, I look back at the vented roof. A morbid wish forms in my heart: that it collapses on top of everyone below. Modern-day Sodom and Gomorrah perishing under a hail of steel beams and polyester roofing sheets. When I get home, I deactivate my main and private Twitter accounts. I post no pictures from that night. If you viewed my IG stories that day, it’s just the caramelized cabbages. It’s like I never left the house.

June 19

When I wake up, I feel a faint scratchiness nibbling at my throat. I immediately have my guard up but tentatively dismiss it as hoarseness from alcohol and shouting. I do not leave my room as a precaution and notify everyone at home.

Today is the point where my life is cleaved in half. I do not know it yet, but this is my last day as a healthy able-bodied person. I will never be the same again.

June 20

I get up for work and notice the soreness in my throat has grown more apparent. I use a rapid antigen test to validate my suspicions. Fifteen minutes later, only a single line. Negative. I show up to work even though something is clearly amiss. Around lunchtime, pain snakes down my lower back. I initially attribute this to poor posture and an office chair with bad back support, but as the day transpires, my head fills with lead and my muscles start to ache. I look over at your cubicle and notice you are quieter than usual. I recall your eerie conversation with the lady at the airport. I book a PCR test for tomorrow. I do not remove my mask at all to drink and I skip lunch to avoid infecting anyone. On the shuttle home, no one sits beside me, a relief. When I arrive home, I have full body aches radiating from my lower back, an elevated temperature, and extreme fatigue. I realize this might be covid and immediately collapse onto my bed. Fitful sleep for 12 hours.

June 21

I wake up feeling better, the worst seems to have already passed, but I am still sick. I now have a headache, a painful sore throat, and phlegm buildup.

I inform the work group chat. You chime in that you are also sick, as I surmised. Our boss says the same and that he hopes I still have the energy for today’s Zoom conference. I cannot say no.

I resurrect my Twitter account in the interest of public health. This is to announce that I have unfortunately but unintentionally ruined your Pride plans. Anyone in contact with me over the weekend should test and isolate.

I contact the work clinic for contact tracing. I inform them that multiple people were coughing yesterday on the same floor and to inform everyone in the shuttle that I was sick. My concerns are downplayed if not outright dismissed, presumably to prevent alarm and another office lockdown. I roll my eyes.

In the afternoon, the Angkas swabber gives me instructions on how to spit in the collection tube. At 2 AM the next day, my RT-PCR results come back positive.

June 22

Symptoms: sore throat, lower back pain, phlegm, runny poop redolent of rotten eggs

I tell you the worst symptom is the throat pain.

You ask me whether I shouldn’t be used to that already.

I tell you I’m posting a thirst trap since you mentioned it’s been so long without one.

You remind me I still have covid.

I say thirst trapping heals my life force.

I recall my time in Cebu, my repeated requests to dine outdoors whenever possible that before were honored, one time holding an inuman session at an outdoor bar we walked and walked to find, but now ignored. But perhaps, even if I were listened to, nothing could have been done to prevent this. We were traveling together, eating together, sleeping together. And more travel awaits me if I stay. Between this and the remote job offer I surreptitiously accepted from under everyone’s noses, I realize that if I stay here, I will get this over and over again.

Later in the evening, I hand in my letter of resignation.

June 23

Symptoms: Lower back pain, sore throat, phlegm, runny poop

Taking vitamins at your insistence. Dropping fluimucil in a glass of water to watch it fizzle.

June 24

Symptoms: Lower back pain, sore throat, runny poop, fatigue

Workmates get tested. Office will only pay for inferior antigen tests. Boss is negative. We are immediately incredulous, voicing our doubts in the employees-only group chat. I don’t believe him, you say. He was coughing all day on Monday. Must be a false negative, I reply. I tested the first day my symptoms appeared and I was also negative.

June 25

Symptoms: Sore throat, phlegm, runny poop, fatigue

Reports of an outbreak from last Saturday’s Pop Emergency at Pop Up circulate. Attendees urged to test and discouraged from attending the Pride marches. Various Twitter users issue a warning that they shall keep a watchful eye on those who were present at the superspreader event yet attend Pride. Gays posting antigen test results all over the timeline. One group declares an all-negative despite one test showing a faint test line. These people aren’t posting results in the interest of public health but to avoid being stoned by an online tribunal.

I deactivate my Twitter account. I am gone for more than 2 months.

June 27

Symptoms: Sore throat, phlegm, fatigue

I send you a meme but you ignore it and ask me how I am.

Me: I’m more than just my disease you know. But to answer you, I’m feeling better.

You: That’s great. How is quarantine life?

Me: I am soaking my mattress in sweat. Going insane.

You: Nice moldy bed.

June 30

Symptoms: Sore throat, phlegm, congestion, fatigue, tachycardia

I virtually present at another conference despite ongoing illness. My heart rate stays above 90 BPM the entire morning. I take my leave and pass out the rest of the afternoon. Something is off.

I continue to work throughout the rest of my quarantine. To this day, I still wonder whether—had I focused on recovery instead of grinding out work—things could have turned out differently.

July 3

I return to the scene of the crime. My fourteen-day quarantine has ended, and work directs me to a testing facility in Pop Up. The acute phase of my infection is over but unbeknownst to me yet, something in my world has shifted. I stop at the entrance and grasp at my chest. It feels like a nail is pushing its way through. I am exhausted but finally test negative. On my way out, I hear a kitten cry. It is frail and tiny with fleas all over, and could not be more than a few weeks old. It is missing an eye. I know it will die soon. I stroke its head. I tell it not to worry, that I feel I will be there with it soon, too.

July 6

At the NBI in Taft for work clearance requirements, I am grasping at anything I can hold onto, lean onto, and sit on. I stand in line for five hours and teeter on the brink of collapse when I am finished. This might have been the worst thing I could have done for my recovery.

July 7

I start bringing my oximeter everywhere: in the long line for the elevator on my first day back at work (104 BPM), during a bathroom break (115 BPM), after a three-hour online speaking engagement (121 BPM). I slowly become aware of the damage that my ostensibly ‘mild’ covid infection has inflicted upon my body.

You are the first person I think about when I start suspecting that something is horribly wrong with me. When you first got infected during the Delta wave and never recovered, frequently catching your breath in exhaustion whenever you spoke, I knew then that Long Covid was real.

Did you ever experience what I’m feeling? I ask you now.

I never had the heart rate issues but fatigue, yes, for a very long time and a heaviness in my body always, you tell me.

Did it ever get better? I’m afraid that this might be permanent.

I remember my friend kept telling me that it gets better, and I really came to a point where I stopped believing in that. But it does get better. You just really need to rest.

I tell you this is good to hear, that at least there is light at the end of the tunnel, even though I cannot see it yet. When did you feel you could say you were already well?

My last attack was in February because I admittedly overexerted myself. For two days, I was out of breath. Around the second week of March, after drowning in Netflix for two months, I started feeling better. But it’s still there sometimes, especially when I am mentally exhausted. My body, especially my joints, will feel heavy. I take it as a reminder to rest.

But can you walk long distances now without fatigue?

Yes. I run and work out now. I recently went hiking and did not feel fatigued.

I come away with the faintest of hopes that that day will come for me too.

July 8

I scour the internet for clues on post-covid conditions that match my heart rate issues. I learn about Dysautonomia, specifically Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome or POTS.

Primarily a pathology of the autonomic nervous system, which regulates certain involuntary functions of the body, POTS manifests as the switching off of the autopilot that steers the circulatory system to pump oxygen-rich blood to the brain upon standing. Instead, blood collects in the body’s nether regions, pooling in the legs and viscera. The brain, sensing this deprivation, floods the system with epinephrine and norepinephrine to constrict blood vessels in the lower extremities and triggers the heart to compensate through an increase in heart rate. But since the autonomic nervous system is in disarray, the body’s attempts at restoring equilibrium do not consummate. No matter how fast the heart beats, the blood vessels in the lower body do not constrict. Blood does not reach the upper body sufficiently and the heart does not cease its forceful beating. Because of the body’s inability to self-regulate, POTS patients can experience an increase of over 30 BPM when transitioning from lying down to an upright position, blood pooling, chest pains, overwhelming fatigue, brain fog, and fainting. Not all symptoms are present in all patients and the experience of POTS ranges from mild to debilitating. The good news: it won’t kill you, but living will suck more than usual, which might make you want to kill yourself. The clincher: there is no cure, or at least not yet, and one can only hope for remission.

Good, I thought sardonically. I did need a new personality.

In the July heat, I stew with this new information, convinced that my life was over when it had barely even begun, and that I was slowly dying, grieving a life I regret I never properly lived.

July 11

At the Heart Center, you tell me the doctor here is young and handsome. He has salt-and-pepper hair and a cool demeanor. I tell him about my symptoms. He catches on and mentions what I have been suspecting, that there have been many patients who, upon recovering from covid, go on to develop POTS. But I wouldn’t know, he adds, his incuriosity puzzling me. I am hooked to an ECG and the results are normal except for tachycardia. I am prescribed further tests, dietary recommendations, and a beta blocker which I refused to take absent a formal diagnosis.

In the lobby waiting for our ride home, I can feel it happening and an internal panic pervades me. I stick my finger in the oximeter and am alarmed to see my BPM hovering in the 120s. I search frantically for a chair and find one outside. I sulk by the window on the ride home, the grief more present and excruciating now, impossible to ignore. At home, I attempt to wring out tears in frustration but come up empty. Elsewhere in life, resignation had become my default, speedrunning the stages of grief and careening straight into acceptance: it is what it is. But somehow, I cannot accept this.

I wonder if things will ever go back to normal. I wonder when I’m going to die.

July 13

Back at the office, on my last day of work, I imagined I’d ask you to stand and give me a hug when I said goodbye to you. But I can hardly stand now, and give you a pat on the shoulder instead.

I demonstrate my symptoms to you like a party trick. When I sit down, my heart rate goes down. When I stand up, it’s like I’m talking to my crush.

I tell you I don’t know when I’ll see you again. I remind you of the bagoong you forgot as pasalubong when you got back from Binmaley all those months ago. I still haven’t shown you how to make sinigang bloody red.

I didn’t know this about me before but I’m glad I know now: I love province boys.

July 16

An article published in The New York Times describes how Emily Sunberg, a 28-year-old editor and filmmaker in Brooklyn, was eating spaghetti when she had a sudden realization: She was being hot.

Hotness, it seems, is no longer in the eye of the beholder. Hotness is a state of mind. In a pathetic attempt to console myself, I become convinced that only hot girls have POTS.

July 17

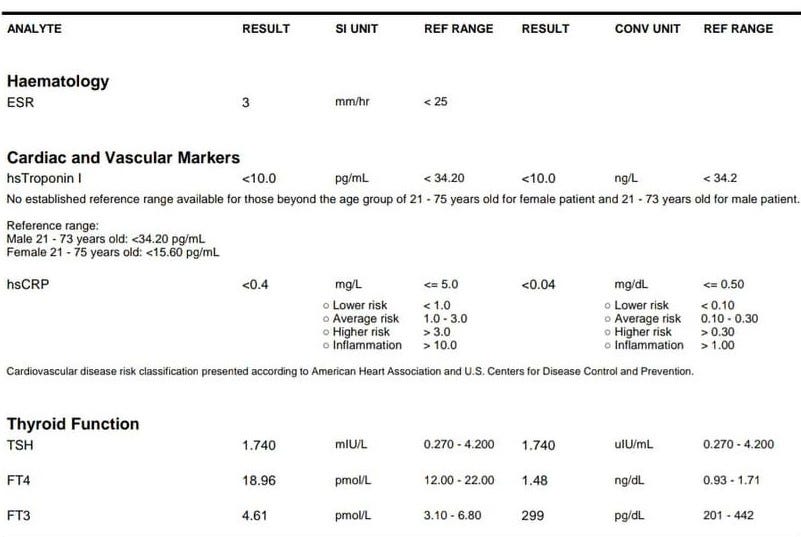

Cardiac and vascular markers and thyroid function are all within normal ranges.

July 18

I joke on the ride home from the doctor’s office and bring up the idea of bringing a foldable chair during protests from now on. There are crutches that collapse into chairs, you know. The last time I was at a demonstration was at the Black Friday Protest after Marcos won the presidency. I escaped from work and found myself in front of a phalanx of riot shields at the CCP. I caught a glimpse of your blue New Balance sneakers as you disappeared into a crowd. You said later that you didn’t see me. But in the pictures you took, I’m standing behind Neri Colmenares with my back to him under a huddle of umbrellas. The next photo you steal of me at a rally, I’ll be in the background, no longer standing, just sitting on the asphalt.

July 19

I start logging my symptoms and triggers in a notebook.

12:00 PM

2 hours sleep deprived

First time sunny after days of rain

Rest BPM = 63 – 65

Standing BPM = 105 – 120

First time in 2 days this is happening again

7:50 PM

Slept for maybe 4-5 hours

Sleep deprivation possible trigger

Standing BPM = 92 – 105

Feeling better, not tired

July 20

2:34 PM

Feeling fatigued

Level 2 mild headache

First time it is this worse again in 2 weeks, I felt I was doing better last week and early this week

Want to cry

Rest BPM = morning, higher than usual @ 80s

2:35 PM = 100 – 110

Standing bpm = AM: 110 – 120

July 21

Stand bpm = 83 – 85

My oximeter broke, this from BP monitor

It is overcast and rainy today

My symptoms are noticeably worse on hot days. On cold rainy days, it’s like nothing is wrong with me. I mull a career in weather forecasting. Heart rate as barometer. Karen Smith can feel it in her boobs, I can feel it in my heart.

July 22

8:00 AM

Rest bpm = 83 (sitting)

Stand bpm = 101

~2 hours sleep deprived

Sun is out again

July 23

AM

Stand bpm = 91 – 92 (via BP monitor)

Sun’s out

2:20 PM

Stand bpm = ~85

Slept from 10 to 1 pm

Cloudy, gonna rain

July 25

Slightly underslept

7:30 AM

Stand bpm = 78

10:30 AM

Stand = 95 – 110

Sit = 74 – 80

July 27

Hot day

T: 31 C, HI: 38 C

2:45 PM

Stand = 100 – 115 (119 at one point)

Sit = 83

Resting BPM higher than normal

POTS patients often have dizzy spells and the most severe cases experience fainting. I was sitting at my desk when my world began to spin. I thought, great, what fresh symptom is this. It was an earthquake.

July 28

It’s only at night when it’s cold that my body feels like its old self. Like a nocturnal animal, I emerge from my burrow to sluggishly haunt the corridors of my house.

I finally have an answer for that Bumble prompt: involuntary night owl.

July 29

POTS patients can handle five times more salt than the average person due to chronic dehydration and lower blood volume. Combined with increased fluid intake, incorporating more salt can reduce symptoms.

I stock up on 2L bottles of Pocari Sweat, Lays, and saltine crackers. Relocate a pitcher from the fridge to my room. Nibble on the edges of Knorr broth cubes and lick salt off my palm. In emergencies, a shot of soy sauce or your cum in my mouth.

August 1

My heart rate jumps to 107 BPM when I get up from bed after masturbating. I could feel the blood drain from my head when I came, my vision blackening. A me-shaped sweat stain has been imprinted on the bedsheet and I am dehydrated. I decide to conduct an experiment: standing at the kitchen counter with a pitcher of water, I drink two full glasses followed by copious gulps of electrolyte-rich Pocari Sweat and a moderately-sized bite of a Knorr chicken broth cube. I stare patiently at the oximeter, focused so intently that my mind drowns out its beeping, and after a minute my heart rate settles down to a comfortable 87 BPM, even going as low as 83 BPM. It was not unlike discovering a superpower.

August 4

Graduated exercise is recommended for POTS patients to progressively build tolerance in maintaining an upright position, beginning with exercises done lying down, sitting, and then standing. While some patients initially lose their ability to walk, even fainting as soon as they stand, I never did. I start taking occasional walks in a park nearby because while standing exhausts me, paradoxically walking does not. In the late afternoon, the air is crisp and at golden hour the light is low and warm. There are people around jogging too and zooming past on bikes. I feel that I can run but decide to take it slow. At the end of my walk, my BPM is in the 100s when I was expecting it to be higher. Not bad. I feel better.

August 5

My compression socks arrive. I do not notice an alleviation of symptoms when using them.

August 6

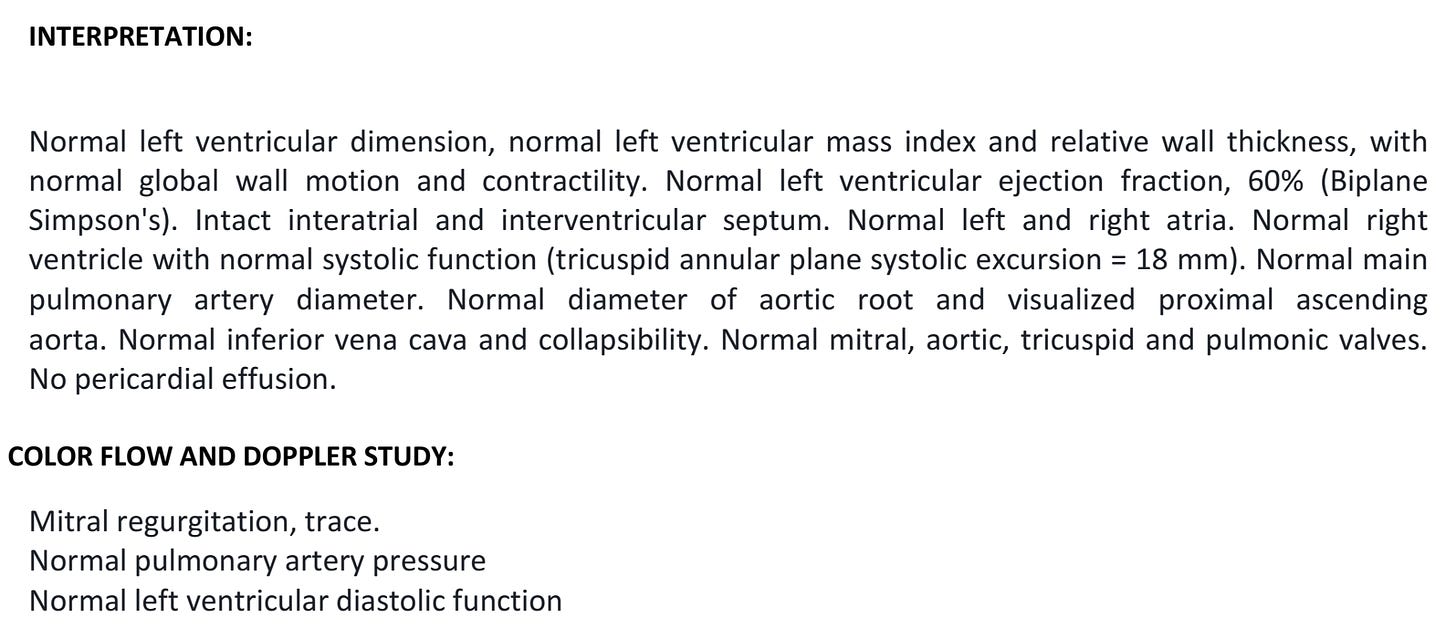

I receive my 2D Echo results:

My heart is healthy. This is unsurprising. After all, POTS is a pathology of the nervous system.

August 7

I have picked up the habit of doomscrolling on POTS support groups on Facebook. It does not do me any good.

One girl shares how she took a short walk to the mailbox, spiking her heart rate to 171 BPM. Used to be a nurse doing 12-16 hours shifts, 5 nights a week in the ER. Numerous people reporting gaslighting and dismissal from medical professionals. Several unable to work.

I dread what the future holds.

August 9

Every day since I tested negative, I have had a dull headache. After today, it vanishes like a bad dream.

August 10

As soon as I feel cold water hit my face in the shower, a soothing calm washes over me. The mammalian diving reflex. Peripheral vasoconstriction, reflex bradycardia, redirection of blood and oxygen to the heart and central nervous system.

My body sinks into the calm, and I am temporarily transported into my old body. I would stay here forever if I could.

August 11

Three hundred and sixty million years ago, the ancestor of modern four-limbed organisms crawled out on lobe fins from the water to land. Eventually, natural selection created evolutionary pressures to develop adaptations beneficial to terrestrial life. Early mammals emerged hundreds of millions of years later. A hundred million years ago, primates diverged from other mammals. Four million years ago, bipedalism evolved, one of the earliest defining human traits. The earliest documented member of the genus Homo, Homo habilis, evolved three million years ago during the Pleistocene. And around three hundred thousand years ago, Homo sapiens emerged in Africa, paving the way for modern-day humans.

Last month, I contracted COVID-19 for the first time. Half a month later, I developed POTS secondary to COVID-19. My ability to stay upright has been compromised since then. I have flunked bipedalism, failed my evolutionary predecessors, wasted hundreds of millions of years of evolution. Something primordial in me yearns to be back at sea, a fish out of water, shed my skin for scales, trade my lungs for gills, rework my limbs for fins and a tail, and never look back.

August 12

I start cooking again. Courgette pasta. I take multiple breaks, bend down to the floor to rest, but I finish cooking through sheer tenacity.

August 20

As a Sagittarius, I cope with humor to bring levity to my unfortunate circumstances à la Lorrie Moore. I contemplate being the world’s first sit-down comedian. There go my plans for a standing desk. That’s all for now.

August 25

9: 43 AM | HI: 37 C

Sit bpm = 99 – 115 (???)

Stand bpm = 115 – 126

August 26

2:30 PM | HI: 39 C

Std bpm = 90 – 97, 100 – 105

Sit bpm = 77 – 80

August 29

Went grocery shopping without incident, heart rate normal.

August 31

It is a cold day but my heart rate is in the early hundreds. I wonder if my recent shopping trip when I was upright for two hours triggered this episode.

September 1

I am not getting better. I’m just getting used to heartbreak.

September 4

Tonight, there will be a Mitski cover gig in Sun Valley, my first foray into the outside world after two months of convalescence. This is to be a test run of me in the wild as a newly disabled person, to see how far I can push myself, tease the limits of my condition, monitor any new symptoms, and determine whether I am a danger to myself alone.

When I get there, it is still raining as it had been the entire day, and despite the cold, I can already feel my chest thumping. I have an emergency bottle of Pocari Sweat in case things go awry and an oximeter in my pocket. Immediately, I regret my choice of outfit: a heavy boilersuit you once called Bilibid-core. It is humid and I am overheating but I soldier through. When the first words of ‘Nobody’ ring across the venue and everyone crowds in front of the band, I cannot immediately tell that I am tachycardic, the booming from the subwoofers dulls the sensation so well I had no idea I had a sustained BPM of 115-120 for hours until I check the oximeter at the end of the gig. I am exhausted and momentarily despair. Outside, sheltering from the rain, watching my BPM refuse to go down on the oximeter, the pent-up denial of my new reality drops from under me as I face what I can no longer ignore: my old body is never coming back. Enter the final stage: begrudging acceptance. While I do not exactly make peace with the injustice of my situation, I acknowledge the need to acquaint myself with my new body, to be kind to it, and to listen and respect it. Tonight, I was in pain, but I didn’t die and I had fun. Maybe it is possible to live with this. Maybe one day, this sadness will fossilize.

September 6

I binge-watch The Bear and it triggers my symptoms.

September 14

October 8

Before I pick you up, I remind you that if anything happens, please find me somewhere to go sit down. There is cold beer from 7/11 in the backseat to pregame, the windows are rolled down for ventilation, my portable HEPA filter is noiselessly humming, and the night is cold. I am already buzzed, partly to avoid the expensive drinks at Elephant Party but mostly to preclude the need to remove my mask. You pull your mask down to your chin as you enter the van and I tell you to hike it back up, you are in my vehicle and should follow my rules. You roll your eyes and begrudgingly say okay. I remind you of my condition and the precautions I need to take. Back when I first told you, after we had made up after another petty fight, you were full of sympathy, had asked me questions, and had done your research. But now you snap back at me, to stop with this, that I am like Katy Perry with her OCD. I ask you if you are calling me a hypochondriac because what I have is actually real. You look at me like I am insane, but it ends there and you comply. I am deeply stunned and hurt, but I ignore it for tonight. Like the gig last month, I cannot tell that I am symptomatic because of the techno music. I manage to dance with no repercussions. I do end up needing your help to find a seat later and you stay with me a bit. Then it’s time for me to go. On the way back to the van, my oximeter shows my heart rate hovering at 143 BPM, the highest it’s been since this all started. I am giddy from alcohol but confused with a sadness I cannot place.

October 10

Pasta carbonara.

October 14

Dilly bean stew.

October 21

Steamed fish with ginger and soy sauce.

I notice I am not as winded anymore after cooking.

October 25

I have since condemned my oximeter to the dresser. I joined a different Facebook group focused on stories of recovery to fend off despair. One post in the group reads, among other encouraging things:

Big victory yesterday! A few months ago, I was fainting multiple times per day. Then yesterday, I went on a hike. We hiked EIGHT miles and I only passed out THREE times! This is a huge improvement and I’m so happy!

Lately, I feel 70% like my old self.

October 28

On October 28, 2022, President Marcos signed Executive Order No. 7 lifting mask mandates that have been in place since the beginning of the pandemic. I am unsurprised but horrified all the same. This is my nightmare scenario. I expect more people to come down with varying degrees of chronic illness or long-term disability in the coming years because of public health policies driven by politics and not science. Apparently, the plan to lift mask mandates was informed by the need for the Philippines to be at par with its ASEAN neighbors who have long since rescinded mask mandates, and not by evidence that suggested that the pandemic truly was over. Immediately, I search whether any NDMOs have released statements condemning the measure. I find nothing even after today. I was already on the verge of inactivity due to illness, merely contributing to statements here and there, but after this, I fully leave the movement completely disillusioned.

November 3

Beef stew with handmade tagliatelle.

November 6

I go to a Halloween Party as Aki Hayakawa from Chainsaw Man, an anime that, together with Spy x Family, heals me with their hilarity.

I am feeling better every day, back to 80% of my former self. Fingers crossed.

November 9

Pasta puttanesca.

November 14

I am learning the guitar. Francis Forever. It calms and distracts me.

November 19

You test positive. I care for you for two weeks as you did for me. I do not get reinfected.

December 1

I am feeling better and better everyday. The path to recovery is rolling smoothly. Most days, I even forget I have POTS. Out of curiosity, I rummage for the oximeter I haven’t used in more than a month. I stand up and check my heart rate: 110 BPM. My day immediately sours. I voice my disappointment in the support group, that I thought I was getting better, but in reality, I was only getting used to the heartache. I despair at how nothing has seemingly changed. Was I living a delusion for the past two months? I thought I had already moved past denial.

Then someone I don’t know sends me a message with reassurance: that it’s great I’m feeling 80% better, to accept that in my mind and to keep moving forward. To take it slowly day by day. I shake off my panic and calm down. I am thankful for the insight and apologize to myself for this moment of weakness. Recovery is not a straight line. Baby steps.

December 10

I arrive early to set up my table. The night has only just begun and it isn’t too crowded yet. I organize my zines on the tabletop, arranging them in neat little rows. My portable air filter blows in my direction as I wait. Soon, the venue starts to fill. I greet my first customer, my first social interaction in weeks, and I am grateful. I watch as more people browse my zines and laugh at my jokes. More sales, more fumbling for change. I see familiar faces and friends I’m seeing for the first time in person. They ask me how I’m doing, that it’s been so long, whether I’m feeling okay now. I tell them I’m doing fine and that I’m glad to see them. I can feel my heart beating loudly in my chest, but this time I know it’s just nerves and excitement. I sell twenty-four copies in total. By the time it’s over, I still don’t want to leave.

When I wake up the next morning, I break down sobbing. The last five months were the most difficult of my life. While I am back to 90% of my former self, I know that I will never be the same, and that’s okay. I am stronger for it. I’m getting better every day and I am happy. I’m glad to be alive.

December 31, 2023

Since my POTS went into remission at the tail end of last year, I have since returned to normal activity levels and have even picked up resistance training. From being symptomatic nearly every day during the first three months of my ordeal with Long Covid, I now only experience my POTS symptoms 10-15 hours cumulatively a month. Yes, my symptoms have not completely disappeared and likely never will. There is no cure after all, but my condition is no longer debilitating.

While I have made a near-full recovery, I have never loosened my covid mitigations. In fact, the more I regain my former health and strength, the more I become protective of them. To contract covid again would be to retraumatise myself and my body and potentially restart the healing process or develop an even more debilitating chronic illness and a worsening of existing symptoms.

I am fortunate that my experience ended in a return to ‘normalcy’, but for millions of people worldwide, Long Covid continues to wreak havoc on their lives. The COVID-19 pandemic is far from over and is arguably the worst it has ever been: the JN.1 variant is currently rampaging across the globe, leaving thousands more disabled and dead, easily infecting populations with immune systems damaged by previous and repeat infections. Surveillance apparatuses have been completely dismantled, mitigations nonexistent, and vaccines continually lag behind exponentially mutating variants and do not provide a bulwark against the development of long-term conditions. With 1 in 10 infections leading to Long Covid, reinfections averaging 1-2 times per year per individual, and with each reinfection causing long-term immune system dysregulation and a cumulative increase in risk of developing Long Covid, it is just a matter of time before most are afflicted.

Meanwhile, the organized left has seemingly succumbed to pandemic fatigue, quietly embracing widespread misinformation and covid-minimizing propaganda from the state, and now tacitly participates in the normalization of mass infection and disability in an embarrassing display of glaring ideological oversight, thereby revealing a tacit satisfaction with the status quo. Ignoring the profound implications of allowing a disabling virus to spread unabated without protest, the left is shooting itself in the foot. How will we organize a revolution if we do not protect our communities from mass disability in a country with already dismal healthcare and meager protections for workers? How will we sustain the armed struggle with deteriorating numbers of healthy recruits when the youth, the inheritors of the revolution, will face the brunt of the debilitating health consequences of repeat infections as they grow? What is being asked from the left, specifically the national democratic movement, is merely a consistent application of its politics and theoretical tools for studying social phenomena (social investigation and class analysis) in arriving at correct ideas on the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

As it is, disabled and chronically ill people face the same indifference from both the state and organizations that were once beacons of community care and safety. For the left to continue to unwittingly participate in collective harm and pandemic normalization is to absolve systemic state neglect and to be complicit in forgetting and revisionism. To capitulate to fatalism and to individualize public health and frame the adoption of mitigations as merely a matter of personal choice and not a political obligation to community care is to invoke the ethos of individual responsibilization undergirding much of this neoliberal hellscape. In short, it is the hallmark of liberalism.

Defeatism is not revolutionary. Fatalism is not revolutionary. Unless the left grapples with these issues, it is a movement and a revolution for able-bodied people only and its claims to radicalism and a scientific orientation are perforated.

In 2024, let us commit to keeping our communities safe. Mandate masking in spaces of resistance. Demand clean air for all. Reject the politics of collective abandonment. Affirm that no one is disposable.

Referring to everyone I interacted with or thought about during this period, sometimes multiple people in the same entry. To preserve the anonymity of those mentioned, I do not mention names.